The Renaissance: Essays

Written By: Amayah Meas

Classical Art & Culture of the Renaissance

Classicism is a style very prominent in all of Renaissance art. Artistic, philosophical, political, and scientific ideas of ancient Greek and Roman cultures were incorporated into European society for centuries leading into the Renaissance, serving as the basis for classical art. Referencing antiquity and historical ideality, sacred subject matter allowed patrons to feel holy and close to Christ. Classicism would influence other art styles in the future, proving to stay relevant as a main influence in Renaissance art.

The architecture in Europe is a great representation of the influence of Classicism on all aspects of society. Buildings like St. Peter’s Basilica designed by multiple artists (Michelangelo and Gian Lorenzo Bernini being some of the most accredited) serve as a main place of worship and gathering and was commissioned by Pope Julius II. This fact reinforces the idea of how art was often tied to patronage and social hierarchies, similar in prominence to that of ancient Greek cultures. Numerous artists collaborated to build this fascinating building for over a century long. Curved arches, columns, and a large dome inspired the templates of other cathedrals and support the construction of the building allowing it to be a lifelong place of antiquity to reference (similar to the Parthenon, the center of religious life in the powerful city of Athens, Greece – its construction dating back to as early as 400 B.C. shows how heavily influential ancient cultures were in European society centuries later).

St. Peter’s Basilica

Michelangelo, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Raphael, & more

c. 1506 – 1626

Iron architecture

Italian Renaissance

Along with architecture, Classicism is incorporated into Renaissance sculpture. Artists began experimenting with a variety of media in the early Italian Renaissance, just as scholarly ideas inspired by ancient Greek and Roman cultures were as well. Donatello was a sculptor that participated in this practice, proving to be one of the most admired artists of the time. He was fascinated with human expression and technical scenarios and began working on the sculpture of David in the mid 15th century. Standing in the contrapposto pose with his weight on one leg while the other remains relaxed and curved (a popular pose used for figural posture in Renaissance art), David is a life-sized, free-standing sculpture serving as the epitome of idealized human figures of the Classical era. The true meaning of the subject matter is left for interpretation, but the overall heroic nudity and biblical association of the sculpture provided a physical model of sacred and political influence for citizens to be reminded of their significance and right to rebel against tyranny.

David

Donatello

c. 1446 – 1460

Bronze

Early Italian Renaissance

Renaissance scholars studied the two notable concepts of Classical sculpture and anatomy in European civilization. The human ideal of mankind was delivered consistently across works of all different media, reinforcing the idea into everyone’s conscience. The Battle of the Nudes is an engraving by Antonio del Pollaiuolo, a highly influential print of multiple naked male figures, all seeming to be slightly varied copies of one man of perfect physical shape. The men are in action, showing off ridiculously flexed muscles that are borderline impossible to naturally attain. The detailed emphasis on muscle (although not quite accurate) of the ten nearly identical figures reflects the interest in anatomical research of artists and scholars at the time. This engraving was embedded into the list of classical ideals for the human to strive towards achieving, along with many other works of different media.

The Battle of the Nudes

Antonio del Pollaiuolo

c. 1465 – 1470

Engraving

Early Italian Renaissance

Classicism was the inspiration for much of Renaissance art from architecture, sculpture, paintings, and other techniques. The apparent human ideals, physically and religiously, were inspired from those of ancient Greek and Roman cultures. This artistic style of antiquity and sacred history carries into much of the later Renaissance and art periods following, showing that classicism in itself is classic.

Sacred Art of the Renaissance

From the 14th to the 17th century, a rebirth of classical philosophies, literature, and art became the center of European society. Patronage was a highly regarded practice and directly related to the strong devotion to religious matters, the subject of much of the art during the period known as the Renaissance. Expression of religious beliefs in art allowed one to strongly connect to Christ and was used for many sacred practices on a day-to-day basis. Sacred art is left open for interpretation but serves multiple purposes with one main goal of showing the societal focus on religion.

Many churches have what is known as an altarpiece, a sacred artwork presenting religious figures meant for placing behind the altar. Altarpieces during the Renaissance served as a good reminder for why people should devote to religion whilst they attended sacred matters. The Altarpiece with Christ, St. John the Baptist, and St. Margaret carved by Andrea da Giona is a relief sculpture; the smooth figures are engraved to reveal themselves as if they were popping out of the background. Although its three sections make it appear like a triptych, its marble panels do not fold closed. Nonetheless, it still serves as an important sacred artwork displaying the figure of Christ with musical angels surrounding Him in the center. St. John the Baptist and St. Margaret are featured on either side and felt deeply associated with the commissioners (Knights of Rhodes) of the artwork, one might say consequently making it a donor portrait.

Altarpiece with Christ, St. John the Baptist, and St. Margaret

Andrea da Giona

1434

Marble sculpture

Early Italian Renaissance

Alongside painting, manuscript illumination prospered during the Renaissance with the escalation in sacred literature. Illuminated manuscripts are books with religious purposes that go through a long, meticulous process of production from the scribe, to illustrators, to decorators. The Book of Hours created by Simon Bening was meant to serve as one of the most, if not the most, prized possessions of its owner. Intended to be used consistently throughout the day, its close proximity and major presence in one’s daily life reminded them of God’s universal influence in them and society all around. As with many other sacred manuscripts, the exceptional miniature detail of the pages (especially because printing presses were not present for this method at the time) shows the lengths artists went to in order to deliver a compelling message.

Book of Hours

Simon Bening

c. 1530 – 1535

Tempera, gold, & ink on parchment

Netherlands Renaissance

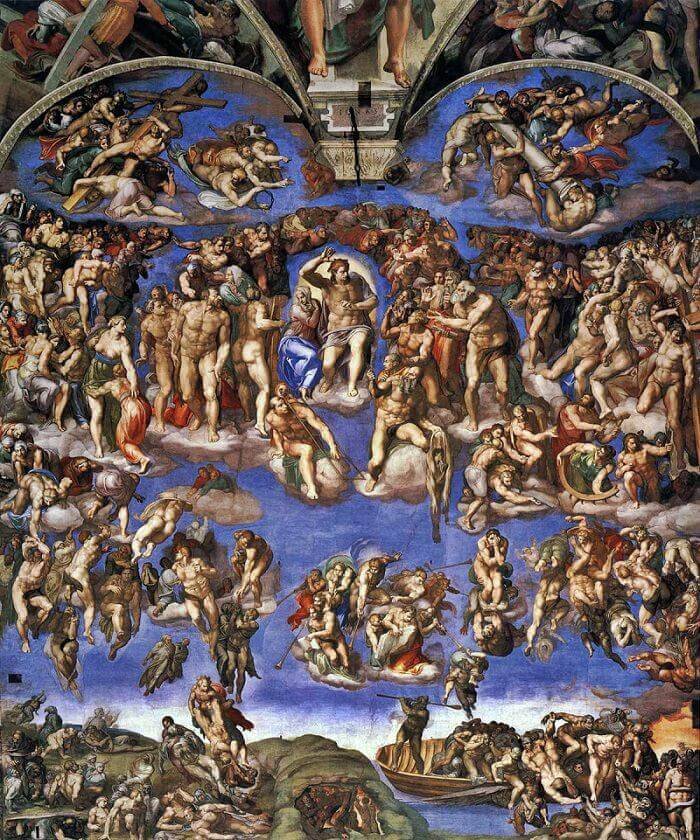

The walls and ceilings of grand religious buildings served as templates for sacred frescos, made with a combination of wet plaster and paint. Michelangelo was a sculptor (an overall talented artist in multiple media nonetheless) who painted the vast majority of the interior of the Sistine Chapel. Following his work of the chapel ceiling, he was commissioned again twenty-four years later by Pope Clement VII to complete the walls, leading to the creation of The Last Judgement. In this painting, the dead are hauled from their graves and plunged into hell, neatly separated from those who are saved and ascend into heaven, all seeming to swarm around Jesus in a vortex. Its sacred subject matter served as a harsh reminder to follow in the footsteps of Christ, lest one’s reality be damned in hell. This fresco contains a scrap of humor as well; St. Bartholomew can be found at the foot of Jesus sitting on a cloud and holding his own flayed skin, reported to contain some of Michelangelo’s own distorted features.

The Last Judgement

Michelangelo

1535 – 1541

Fresco

Italian Renaissance

Sacred art was so prominent in Renaissance culture and was represented in the form of multiple media. As art patronage was a highly regarded factor of society, artists delivered sacred messages in exquisite form to keep religion another top priority for the people. Although its level of influence appears to be stagnant throughout art historical periods, an underlying sacred factor appears to be the base of numerous artworks consistently throughout the Renaissance.

Patronage During the Renaissance

The rebirth of culture, architecture, science, and arts during the Renaissance was the central focus of society starting in the early 14th century. It was a way for people to connect among common beliefs about the world and its creation, along with its creators. This fascination led to the rise and priority of patronage of the arts across society. Much of the middle class embraced patronage due to the explosion of interest in literature and creativity. Wealthy patrons (clients who commissioned or bought artwork) held an unspoken authority in society as well, due to their high-class status and power driven by money. During the Renaissance, patronage of the arts was fueled by societal devotion to religion and scholarship and was a way for high class socialites to show off their status.

Although architecture was not as prominent during the Early Renaissance due to the lack of engineering skills and knowledge, scarce luxurious buildings were still present and held the noblest of society. In Florence there existed the Medici family, a group of wealthy merchants with immense power and leadership in the realm of intellectual and artistic patronage. Cosimo the Elder of the Medici family commissioned Michelozzo di Bartolomeo to construct the Palazzo Medici Riccardi, a grand palazzo, or palace, of residence that also served as their place of business and gathering for important political figures. Although they were not societal leaders by law, their high-class status unofficially named the Medici rulers of Florence, and their palazzo delivered this message effectively to all of Florence and beyond, sparking conversation among its passersby and ultimately being noted on the same level of nobility as other grand cathedrals at the time. The Medici are not physically displayed on the building itself, but its rustic stone block architecture and detail of sgraffito work clearly manifests their authority while also incorporating Classical elements inspired by ancient Roman ruins and referencing the antiquity, harmony, and ideality of early Renaissance architecture.

Palazzo Medici Riccardi

Michelozzo di Bartolomeo

1446 – 1460

Rusticated stone block architecture

Early Italian Renaissance

Over in Rome, Pope Julius II commissioned Florentine sculptor Michelangelo to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in 1508. Although not pleased with the task because of his customary gravitation towards sculpting, Michelangelo nevertheless spent the next four years achingly lying on a mobile wooden scaffolding designed to move across the ceiling in order to paint under the order of a patron of such nobility; the task’s mere difficulty demonstrating the seriousness of artistic patronage during the Renaissance. With the chapel serving as a place of worship, Michelangelo includes numerous scenes from the Bible that beautifully depict classical figures of the Old Testament with an illusionistic marble form that reference his sculpting roots. Individual scenes of the massive ceiling are continuously examined for their subject matter, and its overall creation established a new, powerful style in Renaissance painting.

Sistine Chapel

Michelangelo

1508 – 1512

Fresco

Italian Renaissance

Many wealthy patrons sought to see themselves alongside holy figures in the art they commissioned to demonstrate their religious devotion and connection to Christ. In the latter half of the 15th century, Tommaso Portinari, head of the Medici bank, commissioned Hugo van der Goes to paint a grand altarpiece for the Portinari family chapel. The extraordinarily large triptych is a three-piece set of wooden panels hinged together which display numerous members of the Portinari family praying by the Nativity scene with the newborn Christ, the Virgin Mary and Joseph, and other angels and shepherds (simultaneously making this artwork a donor portrait). The iconography of the Portinari Altarpiece makes it extremely notable to this day, and the prominence of the patron saints displayed by their similarity in scale to that of the holy figures demonstrates the extent to which artistic patronage elevated the lives of people during the Renaissance.

Portinari Altarpiece

Hugo van der Goes

1475 – 1478

Oil on wood panel

Early Italian Renaissance

Patronage is a prevalent theme during the Renaissance that demonstrates the importance of arts during this rebirth of Classical culture in Italy. The extensive accomplishments of artists demonstrate its importance to wealthy patrons who held their high societal status tied to the art they commissioned, concurrently representing the intellectual and religious devotions that fueled the artistic community.

The Illusion of Space During the Renaissance

During the 15th century, patron and artists’ appreciation for individual human intellect and achievements of the classic world heightened. People began to collect art for personal enjoyment, contributing to the increase in presence of patronage as a public activity. During this time, a new fascination of Renaissance painters was to present idealized figures (inspired by the Classical antiquity of the past) in a realistic manner throughout the space within a picture plane. Influenced by the societal value of scholarship, a new Renaissance perspective became the basis for art in Italy.

This “Renaissance perspective” is defined as achieving lifelike illusions of reality and idealized figures analytically using a system of linear perspective, where receding space is arranged in conformity and is posed to align with implied lines that would converge at a single vanishing point. In other words, this mathematical technique was used to represent three-dimensional figures in a two-dimensional space. Linear perspective revolutionized the art world by allowing artists to achieve such a concept, something new and fascinating to both artists and spectators. Masaccio's Trinity with the Virgin, St. John the Evangelist, and Donors is a well-known painting presenting figures that are measured in a specific progression using this technique that allows one to view it as if it were an extension of their own space. The hieratic scale of the piece also represents the order of social and life statuses with Christ at the top, the Virgin Mary & St. John following, and finally the donors at the bottom, showing how linear perspective can be used not only to depict three-dimensional space but also to acknowledge popular societal practices at the time.

Trinity with the Virgin, St. John the Evangelist, and Donors

Masaccio

c. 1425 – 1427

Fresco

Early Italian Renaissance

Nearly two centuries after mathematical perspective became widely adopted in Renaissance painting, the technique still remains relevant. Artists expanded on this concept by utilizing a view from the corner of a frame rather than the front, demonstrated by Tintoretto’s version of The Last Supper. Previously done by Andrea Del Castagno and Leonardo Da Vinci, Tintoretto reinterprets the same subject displayed from the corner of the space with a vanishing point in the upper far right, while also using different forms of luminosity and color (consistent with the Mannerist tendencies of the era) to reveal the figures. The orthogonals, or implied perpendicular (of the picture plane) lines, remain consistent with the analytical technique and is a nice example of its variations used to offer multiple perspectives of the same scene.

The Last Supper

Tintoretto

1592 - 1594

Oil on canvas

Italian Renaissance

Before artists could achieve linear perspective in art, the concept of space on a flat plane was depicted using a technique called intuitive perspective. Artists would present figures with decreasing size as they fade into the background to imply receding space in the distance, simply with the eye rather than mathematics. The Limbourg brothers demonstrate this well in the February page of Les Trés Riches Heures, showing a chilly winter scene. In the foreground, peasants seem to be enjoying the heat of a fire while others in the distance continue to work. The sky in the background depicts an atmospheric perspective as well, as the hues of blue are transitioned into one another to show the natural effects of the atmosphere on things in the distance. The largest figure appears to be the woman sitting closest to the front, clothed in an elegant garment implying she is not a peasant, reiterating the idea that perspective techniques are used to depict social statuses as well.

February: Life in the Country, Trés Riches Heures

Limbourg Brothers

1411 – 1416

Colors & ink on parchment

Early French Renaissance

From the early years of the Renaissance to the latter and beyond, artists use the concept of perspective to represent three-dimensional space on a flat picture plane. As time went on, advances in analytics/mathematics, a stronger appreciation for artistic patronage, and desire to depict figures more realistically contributed to various perspectives. Numerous artworks beautifully presented demonstrate each one, branching off the previous technique while aligning with the progression of societal ideals.

References (Classical Art & Culture of the Renaissance)

Encyclopedia Britannica, inc. St. Peter's Basilica. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved October 22, 2021, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Saint-Peters-Basilica.

History.com Editors. (2018, February 2). Parthenon. History.com. Retrieved October 22, 2021, from https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-greece/parthenon.

St. Peter's Basilica - opening hours, price and location – rome. Rome by CIVITATIS. Retrieved October 22, 2021, from https://www.rome.net/st-peters-basilica.

Classical art and architecture - history+. The Art Story. Retrieved October 22, 2021, from https://www.theartstory.org/movement/classical-greek-and-roman-art/history-and-concepts/.

Cartwright, M. (2021, October 21). Ancient greek society. World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved October 23, 2021, from https://www.worldhistory.org/article/483/ancient-greek-society/.

Marilyn, S. (2011). Art history: Fourteenth to Seventeenth Century art. Prentice Hall.

References (Sacred Art of the Renaissance)

Altarpiece with Christ, Saint John the Baptist, and Saint Margaret. Metmuseum.org. Retrieved October 23, 2021, from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/471909.

Book of Hours. Metmuseum.org. Retrieved October 23, 2021, from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/684184.

Italian Renaissance Art - Fresco Painting. Italian renaissance art - fresco painting. Retrieved October 23, 2021, from https://www.artyfactory.com/art_appreciation/art_movements/italian- renaissance/italian-renaissance-art-fresco-painting.html.

Manuscript Illumination in Italy, 1400–1600. Metmuseum.org. (n.d.). Retrieved October 23, 2021, from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/iman/hd_iman.htm.

Marilyn, S. (2011). Art history: Fourteenth to Seventeenth Century art. Prentice Hall.

References (Patronage During the Renaissance)

The palace. Palazzo Medici Riccardi. (2018, September 13). Retrieved October 15, 2021, from http://www.palazzomediciriccardi.it/en/palace/.

Medici Riccardi Palace. Florence. Retrieved October 15, 2021, from http://www.museumsinflorence.com/musei/medici_riccardi_palace.html.

Encyclopedia Britannica, inc. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved October 15, 2021, from https://www.britannica.com/place/Palazzo-Medici-Riccardi.

Michelangelo's painting of the sistine chapel ceiling. ItalianRenaissance.org. Retrieved October 15, 2021, from http://www.italianrenaissance.org/a-closer-look-michelangelos-painting-of-the-sistine- chapel-ceiling/.

Howard, D. R., & Howard, D. R. Hugo van der Goes, Portinari Altarpiece. Smarthistory. Retrieved October 15, 2021, from https://smarthistory.org/van-der-goes-portinari/.

References (The Illusion of Space During the Renaissance)

The holy trinity (1428). Holy Trinity, Masaccio: Interpretation, Analysis. Retrieved October 22, 2021, from http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/famous-paintings/holy-trinity-masaccio.htm.

Khan Academy. Masaccio, Holy Trinity (article). Khan Academy. Retrieved October 22, 2021, from https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/early- renaissance1/painting-in-florence/a/masaccio-holy-trinity.

Il Tintoretto: The last supper. ArtBible.info. Retrieved October 22, 2021, from https://www.artbible.info/art/large/353.html.

Khan Academy. Limbourg brothers, Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (article). Khan Academy. Retrieved October 22, 2021, from https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance- reformation/northern-renaissance1/limbourg-brothers/a/limbourg-brothers-trs-riches-heures.

Bolli, C. M., & Bolli, C. M. Limbourg brothers, Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. Smarthistory. Retrieved October 22, 2021, from https://smarthistory.org/limbourg-brothers-tres-riches-heures- du-duc-de-berry/.

Marilyn, S. (2011). Art history: Fourteenth to Seventeenth Century art. Prentice Hall.