The Baroque: Essays

Written By: Amayah Meas

The Baroque’s Depiction of Light

The Baroque period is one of the most remarkable styles of art that revolutionized the world of painting, architecture, sculpture, and design. One of the techniques most commonly attributed to Baroque painting is tenebrism, the use of intense chiaroscuro that shines a spotlight on certain parts of a painting to indicate a potential meaning of the subject matter. The use of light has proven to transform the iconography of a painting, especially when interpreted by multiple artists (for example, The Last Supper, painted by Andrea del Castagno, Leonardo Da Vinci, and later, Tintoretto), and adds a sense of depth due to the dramatic details and emotions it entails.

Caravaggio was an Italian painter most notably recognized for his immense contribution to the Baroque period. Depicting powerful yet ambiguous subject matter in paintings using realism and theatrical lighting techniques, spectators are left in awe after viewing one of his works. Caravaggio’s revolutionary take on painting would lead to the formation of the Caravaggisti, a group of followers that took inspiration and/or imitated the artistic style of Caravaggio, even without ever knowing or working alongside him. Caravaggism would disseminate across Europe by Italian and non-Italian painters, showing the impact of his expertise (Khan Academy). Bacchus by Caravaggio is a portrait of a young boy dressed in heavy drapery, offering the viewer a glass of wine. The depiction of his upper half, (a composition that would later be imitated by similar artists) is defined by the soft highlight that separates him from the background. His image is idealized yet realistic, having plump and smooth skin, rosy cheeks and lips, and perfectly carved eyebrows which juxtapose his muscular arm. One may wonder why such a youthful figure sits alongside aging fruit, perhaps it indicates the realization that life is temporary? The ambiguity of Caravaggio’s painting aligns in competence with that of his techniques, paving the way for his influence in the art world.

Bacchus

Caravaggio

1595 – 1596

Oil on canvas

Italian Baroque

Genre scenes were a popular style of painting during the Baroque period, depicting realistic moments from everyday life. Spanish painter Diego Velázquez painted Las Meninas in 1656, which shows King Philip and his queen’s daughter, Infanta Margarita, surrounded by her attendants. The royal couple and even Velázquez himself is shown in this painting, reflected in the mirror and (the latter) standing near a large canvas. Simply trying to interpret the composition of the subject matter is a fascination in itself; it appears as if we (the spectator) may very well be the King and Queen standing before our daughter who stares back at us, with Velázquez on the left painting the very portrait that is depicted here (Harris, Zucker). A light appears to be coming from the right side of the painting and shines directly on the centered young princess, creating shadows and indicating her as the focal point of the painting. One may even hone in on her eye contact along with that of Velázquez with the viewer, evoking an eerie yet inviting emotion. This interpretation takes the Baroque style of including the spectator in the same realm as the subject matter to another level, due to the depiction of light on notable features of the characters.

Las Meninas

Diego Velázquez

1656

Oil on canvas

Spanish Baroque

The Dream of Aeneas painted by Salvator Rosa, a history painting, tells the story of Aeneas who sleeps on the banks of the river Tiber. The God of the river, Tiber himself, kneels above him and carefully whispers that Aeneas will build his future city at this spot (Metmuseum.org). The use of light (or lack thereof) highlights the slightest parts of subject matter. Aeneas’ armor is featured dim and worn, emphasizing his exhausted state while the small patch of sky in the upper left reveals the dreary mood. It is interesting to note that Tiber himself is nearly depicted with the same amount of light as Aeneas (or even darker in fact), perhaps showcasing the idea that they have similar levels of capabilities and power in mythology.

The Dream of Aeneas

Salvator Rosa

1660 – 1665

Oil on canvas

Italian Baroque

The usage of light to highlight the importance of subject matter is evident in Baroque painting. This technique creates room for multiple interpretations and paved the way for future artistic styles and movements. Significantly, the depiction of light dramatically enhances the spectator’s experience, drawing emotional and intimate reactions which satisfies a prominent goal of the Baroque period.

Secular Subject Matter of the Baroque

For centuries leading into the Baroque period, the Renaissance dominated European society and culture. Beginning circa 14th century, the Renaissance was a rebirth of ancient Greek and Roman philosophy, art, and literature. The artistic style incorporated these values while taking inspiration from the Classical past and focused on depicting idealized yet somewhat realistic religious figures and scenes from scripture. Around circa 17th century, the Baroque period began, which also focused on presenting religious scenes, yet in a unique way than the Renaissance. Using dramatic elements and techniques, artists of the Baroque period aimed to evoke symbolic meaning and emotional reactions from the spectator, making them feel as if they were in the same realm as the subject matter.

Perhaps due to increased access to greater brushes and paints, Baroque artists were able to depict meticulous detail of facial expressions to a level more complex than that of the Renaissance. Branching off the idea of an increased societal interest in scholarship and science, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp painted by Rembrandt Van Rijn in 1632 depicts a genre scene in which Dr. Tulp teaches seven curious and awestruck men about the human anatomy with a physical diagram of the muscles of a cadaver’s arm, a typical scholarly activity (Zygmont). Tenebrism is a common technique used throughout Baroque paintings – the intense chiaroscuro distinguishes the focal point of the subject matter with a spotlight that appears to be coming from the world of the spectator. The cadaver’s parallel position to the picture plane sets him apart from the others, and the luminosity of his body identifies him as the focus (along with his dissected arm drawing the most attention). Dr. Tulp can be identified as a secondary focal point. His authority is implied by being the only man with a hat and pointing to the arm as he lectures to the others. The details of each man’s facial expression are so intricate that they project deeply personal and psychological emotions, and the two men in the background make eye contact with the viewer, contributing to that intimate experience for the spectator.

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp

Rembrandt Van Rijn

1632

Oil on canvas

Dutch Baroque

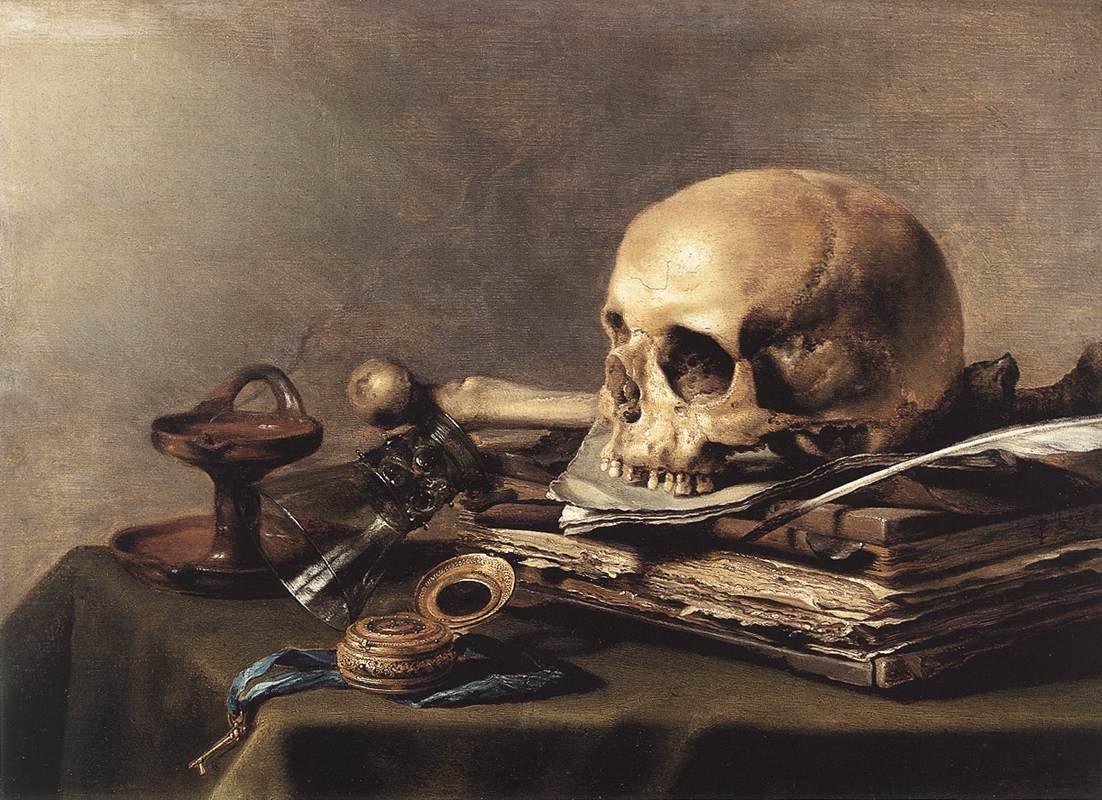

Another genre of painting popularized during the Baroque period was still life: paintings with subject matter consisting of ordinary inanimate objects. Artist Pieter Claesz was known for his wide range of still life paintings, specifically vanitas paintings, ones where the subject matter intended to symbolize themes relating to mortality and the transience of life. Claesz’s Vanitas Still Life painted in 1630 consists of numerous objects relating to such a theme. The skull (the focal point of the painting highlighted by a light source from the up left corner) is distinguished by subtle tenebrism and serves as a memento mori, a symbolic trope commonly used to remind spectators of their inevitable death. The time piece in the foreground similarly represents the theme, as if time were ticking down until one’s life is up (literally). The quill, paper, key, and toppled cup are common items in everyday life, their cluttered composition relates to the realistic connection of the viewer in Baroque style painting.

Vanitas Still Life

Pieter Claesz

1630

Oil on panel

Dutch Baroque

In circa 1634, Diego Velázquez painted a history painting called The Surrender of Breda, showing the close interaction between the Dutch and Spanish militaries. The landscape depicts what appears to be the end of a war as clouds of smoke dissipate into the blue sky. Numerous assumptions can be made about the two groups; the Dutch on the left seem disorganized and few in number while the Spanish on the right is orderly and dominant in number (due to the excess of spears flowing into the distance)(Berzal). Velázquez’s use of earth tones and soft exposure present the painting in a very naturalistic manner. A few soldiers from both sides are slightly highlighted and make eye contact with the spectator, creating an experience as if they were present in the scene.

The Surrender of Breda

Diego Velázquez

c. 1634

Oil on canvas

Spanish Baroque

In multiple genres of painting, artists were able to depict realistic subject matter with elaborate detail in the Baroque period. Baroque style is distinguished from that of the Renaissance because of the dramatic lighting techniques and compositions designed to include the spectator in the experience. By expanding on past concepts and historical periods, artists were able to evolve the art world and transform it to capture more themes.

Architecture of the Baroque and Rococo Periods

Although architecture throughout the Baroque and Rococo periods have evolved over time, an aspect many constructions have in common is that they are used to signify a symbolic meaning, in addition to its functional purpose. This symbolic meaning is usually the social status of its commissioner or inhabitant, shown by the valuable designs most consistent with the period it was built. Architectural designs from the past can be examined to understand the values of people, and what society was like during that time.

Nearing the end of the Renaissance, the Catholic Counter Reformation emerged, a religious movement purposed to oppose the Protestant Reformation and rebuild the Catholic Church and its authority. In the early 17th century, architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini built St. Peter’s Baldachin, also known as Baldacchino, which is a canopy typically placed over an altar or throne. This massive bronze sculpture is inside St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City, the center of Roman Catholicism. The architecture is eight stories high, marking the center crossing of the church between the nave and the transept and stands right below Michelangelo’s dome (Harris, Zucker). It is one of two primary altars, one of the places the Pope would hold mass. Being the focal point of the space, it signifies the burial of St. Peter below and the Catholic Church as the ultimate authority in the Vatican.

St. Peter’s Baldachin

Gian Lorenzo Bernini

1623 – 1634

Sculpted bronze

Italian Baroque

Over a century later after the opening of St. Peter’s Basilica, the Salon de la Princesse was designed by French architect Germain Boffrand. Consistent with the delicate and airy styles of the Rococo period, the room is decorated with light, pastel ornaments and detailing. This private salon was used to hold intimate gatherings for people of high status. It resembles a rotunda, a style of architecture with a round floor plan, typically topped by a dome. The minimalist and feminine interior design reflects the tendency to depict noble women in a decorative, elegant way with luxurious clothing and lavish backgrounds (typical in Rococo salon culture) (Brighidin, 2012). Aside from the main purpose of holding stylish meetings, an underlying yet prominent meaning of the architecture was to boast the fancy and superior statuses of its tenants.

Salon de la Princesse

Germain Boffrand

1732

French Rococo

Another example of French nobility shown through architecture is the Palace of Versailles – yet this building is the most over the top. King of France, Louis XIV, commissioned the construction of his new palace in Versailles, a city in France which solely signifies the King’s importance. This palace represents the utmost excess of French nobility, with every detail catering towards King Louis’s desires. According to an article from Khan Academy, this massive establishment contains 700 rooms, 2,153 windows, and takes up approximately 67,000 square meters of floor space. Its placement along the east and west axis is designed to align with the rise and set of the sun. The gardens and interiors are filled with marvelous sculptures, paintings, and fountains lined with marble and gold accents to remind its inhabitants of the King’s wealth wherever their location in the palace. Its designs reflect classical elements inspired from ancient Greek cultures, believed to be the root of all intellectual and aesthetic authority that flowed into French culture. The Palace of Versailles is the most extensive statement of status in France and has communicated that message every day forward from its construction. It incorporates classical details while staying relevant with the ornate gold accents at the time, reflecting King Louis XIV’s ultimate authority.

Palace of Versailles

André Le Nôtre, Louis Le Vau, more

1634

French Baroque

Architecture and interior design are used as means of communicating one’s style, status, and wealth, demonstrated by numerous constructions throughout art historical periods. The designs may take inspiration from past styles and concepts while staying relevant with their time, whether that be the dramatic detailing of the Baroque period or the light and pastel accents of Rococo. For centuries, architecture has held functional and symbolic meanings and serve as important historical landmarks to understand the zeitgeist of the times.

References (The Baroque’s Depiction of Light)

Bacchus, 1596 by Caravaggio. Retrieved December 9, 2021, from https://www.caravaggio.org/bacchus.jsp.

Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, Harris, D. B., & Zucker, D. S. Khan Academy. Velázquez, Las Meninas (video). Khan Academy. Retrieved December 9, 2021, from https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/early-europe-and-colonial- americas/reformation-counter-reformation/v/vel-zquez-las-meninas-c-1656.

Khan Academy. Caravaggio and Caravaggisti in 17th-century Europe (article). Khan Academy. Retrieved December 9, 2021, from https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance- reformation/baroque-art1/baroque-italy/a/caravaggio-and-caravaggisti-in-17th-century-europe.

Metmuseum.org. Retrieved December 9, 2021, from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437507.

References (Secular Subject Matter of the Baroque)

Artst. (2021, September 5). Renaissance vs baroque art - what's the difference? Artst. Retrieved December 3, 2021, from https://www.artst.org/renaissance-vs-baroque-art/.

Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Vanitas. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved December 4, 2021, from https://www.britannica.com/art/vanitas-art.

Khan Academy. Velázquez, the surrender of Breda (article). Khan Academy. Retrieved December 3, 2021, from https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance- reformation/baroque-art1/spain/a/velzquez-the-surrender-of-breda.

Tate. (1970, January 1). Vanitas – art term. Tate. Retrieved December 4, 2021, from https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/v/vanitas.

Zygmont, D. B., & Zygmont, D. B. Rembrandt, the anatomy lesson of dr. Tulp. Smarthistory. Retrieved December 3, 2021, from https://smarthistory.org/rembrandt-anatomy-lesson- of-dr-tulp/.

References (Architecture of the Baroque and Rococo Periods)

Bianchi, H. (2020, December 2). Bernini's Baldacchino is actually A ciborium. Catholic Review. Retrieved December 4, 2021, from https://catholicreview.org/berninis-baldacchino-is-actually-a-ciborium/.

Brighidin, S. The hierarchy of Rococo women seen through fashion paintings. Cornerstone. Retrieved December 4, 2021, from https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/jur/vol12/iss1/1/.

Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, Harris, D. B., & Zucker, D. S. Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Baldacchino, Saint Peter's. Smarthistory. Retrieved December 4, 2021, from https://smarthistory.org/bernini- baldacchino/.

Khan Academy. Château de Versailles (article). Khan Academy. Retrieved December 4, 2021, from https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/early-europe-and-colonial- americas/reformation-counter-reformation/a/chteau-de-versailles.

McKay, S. (1994). The "Salon de la Princesse": "Rococo" Design, Ornamented Bodies and the Public Sphere. Vol. 21, pp. 71-84. Retrieved December 4, 2021, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/42631189?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.